At the turn of the millennium, Jean Carnahan, the first lady of Missouri, ushered in the new year with a profound sense of loss.

Her husband had just been elected to the United States Senate, despite having passed away in a plane crash, just three weeks before election day.

In the 2000 United State Senate election for Missouri, her husband, Mel was elected with 50% of the vote compared to Republican incumbent John Ashcroft’s 48%. Before running for the Senate, Mel Carnahan had been the 51st governor of Missouri, its second to last Democratic governor to date. Mel maintained high approval ratings throughout his tenure, supporting progressive policies like abortion rights, gun control, and education reform.

After Carahan’s passing, red buttons transcribed with the words “I’m Still with Mel” spread across the state. Polling places were left open for two extra hours in order to account for the high voting turnouts in cities like St. Louis.

Jean, claiming her husband’s victory, promised supporters that she would “never let the fire go out,” a recall to one of Mel’s most common sayings.

John Ashcroft is the only United States Senate candidate to be defeated by a deceased person, no less a Democrat, in a state now dominated by state-wide Republican politicians, a symbol for how Missouri politics have drastically shifted in the last decade and what Missourians still have to learn.

It would be unimaginable today to see a Democrat hold statewide office in Missouri, no less a deceased Democrat.

Let’s not forget that Republican John McCain won over President Barack Obama by only 4,000 votes. Missouri used to be a highly contested bellwether state, predicting how the nation would vote for the president with great accuracy until 2008.

Since then, Missouri has been secured into a Republican stronghold, holding a ruby red majority in the two state legislatures and the governorship. Missouri has not elected a Democrat to a state-wide position since 2018.

Following the 2024 election, Democrats suffered losses across the state, despite intricate planning and funding.

Democratic Senate candidate Lucas Kunce lost against Republican incumbent Josh Hawley despite outraising him in campaign donations. Nevertheless, progressive ballot initiatives like Amendment 3, that would enshrine abortion access in the Missouri constitution, were passed, likely on the same ballots supporting anti-abortion candidates.

According to Pew Research Center, 80% of Americans believe that elected officials don’t care what people like them think. The results of the study saw a large increase in this belief from a similar study conducted in the early 2000s.

The study suggests that Americans lack trust in their officials, and feel like they have little influence in their local governments compared to special interest groups or wealthy donors.

This disconnect between voters and legislators, especially on the local level, is not a new feeling among Americans, especially in Missouri counties where partisan politics dominate and isolate even right-leaning voters that make up our Republican majority.

Missourians are frustrated with the, often partisan driven or divisive, choices that they have to make for each election, that try to portray them as single-issue or monolithic. This pattern of conflicted voting, specifically regarding Amendment 3 evokes the time of Mel Carnahan.

The proposal for an abortion amendment was sent to Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft’s office in May of 2024, after more than 380,000 signatures were collected by Missourians for Constitutional Freedom, the group behind Amendment 3. Missouri was one of 13 states with trigger laws regarding abortion, meaning the state underwent a complete abortion ban when Roe v. Wade was overturned. After the overturn of Roe v. Wade, nearly all abortions were banned in Missouri.

The amendment was able to pass with the help of split-ticket voters. In St. Charles County, the most accurate bellwether area in Missouri, voters demonstrated this struggle between their own interests and the familiarity of partisan politics by voting for both the progressive Amendment 3 and Republican officials.

St. Charles County was one of four counties who voted for both expanding abortion access through Amendment 3 and Donald Trump, alongside Buchanan, Clay, and Platte counties.

This voting phenomenon provides commentary on the often unrepresentative politicians Missourians vote into office.

Incumbency advantages are extremely strong in red areas like St. Charles County, where Congresswoman Ann Wagner has represented Missouri’s 2nd congressional district since 2013, easily winning re-election each year. Wagner has even expressed her intent to run for re-election in 2026, for what would be her 7th term. Her district voted within 10% of the statewide vote, accurately representing the state vote on Amendment 3, though also voting in Wagner, who opposes abortion rights.

It is in these districts that voters rely on party recognition rather than candidate alignment or even plain name recognition.

Voting with party influences in mind fuels inattentive politicians, who opt for reaching constituents through campaign ads or yard signs instead of meaningful or representative policy.

While Amendment 3 ultimately passed, but not without challenge from Missouri politicians.

As abortion rights supporters were working to gain the signatures they needed to be on the November ballot, the Missouri General Assembly was attempting to make the constitutional amendment process even harder.

In February 2024, the Missouri Senate tried to pass a bill requiring that only United States citizens be allowed to vote and that prohibited foreign interference in the initiative petition process.

These provisions were called “ballot candy” by Missouri Senate Democrats. They branded those conditions as an attempt to get more resolution support, since citizenship is already a voting requirement and foreign interference is already banned by federal law.

The Democrats performed a 15-hour filibuster to remove them. The bill was passed onto the Missouri House of Representatives, with only one Missouri Senate provision that increased the amount of votes needed to pass a constitutional amendment.

But, the House amended the bill to include the deleted terms, in addition to adding a provision requiring that constitutional amendments have support from five of Missouri’s eight congressional districts. Six out of eight districts are red.

Back in the Missouri Senate, a 50-hour filibuster from Democrats saw the end of the legislative session without a vote, effectively killing the bill.

Later, the ability of Amendment 3 to appear on the November ballot was still tentative.

Despite having previously certified the proposed amendment, Jay Ashcroft wrote to Missourians for Constitutional Freedom lawyer Tori Schafer, decertifying the amendment. He cited an earlier circuit court’s decision declaring the amendment as inadequate since it did not mention what laws it would appeal.

This judgement was ultimately reversed by the Missouri Supreme Court, forcing Ashcroft to put the amendment on Missouri ballots.

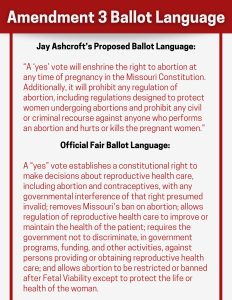

Around the same time, Ashcroft, who is vocal against abortion, was forced to remove his “misleading” ballot language by the order of a circuit judge. Circuit Judge Cotton Walker would write new ballot language to appear at every polling place.

Opponents of the abortion measure, namely Republicans, have tried to attribute its success to the $31 million raised by Missouri for Constitutional Freedom, the PAC behind Amendment 3. But, this claim is disregarding how Amendment 3 was passed precisely with the help of Missouri voters from all political backgrounds, since 3 million Amendment 3 voters also voted for Trump. The claim assumes that Missourians were driven by campaign funded appeals, rather than their own wants, again maintaining discontent between legislators and voters.

This strange alignment between Amendment 3 votes and conservative votes suggests a tendency to rely on voter-driven ballot initiatives or people-led movements rather than trusting the public officials that we vote into office.

Not only does this reinforce distrust in politicians, it also weakens any Democratic, and possibly more representative holds in the state. As more progressive ballot initiatives are passed, there are fewer policies Missouri Democrats can run on. In this stead, politicians who do not represent or even oppose the wills of Missourians are increasingly elected.

There is hope though. The 2024 election saw record numbers of voter registrations and constituents in line to vote on election day for St. Charles County. Missourians not only voted for Amendment 3, but fought for its passage.

Though their ballots may be at odds with their interests, these votes and the passing of legislation like Amendment 3, point to an optimistic embrace of voter responsibility.

It is times like these that exemplify the ways that Missouri voters have not changed since Mel Carnahan was elected, that show how Missourians do not settle for the obvious choice, and do not let the fire go out.

It is the results of the 2024 and 2000 elections that tell us to not settle for familiarity, but to instead walk the political path that seems impossible.

In the face of her husband’s victory, Jean Carnahan declared that “the mantle has fallen on us” a statement that rings more true than ever, as modern voters realize the true power their ideas, beliefs, and ballots hold. Again, the mantle has fallen on us and our power to vote for what and who we want to represent us and our will.

In a tribute to her father, Robin Carnahan wrote about having walked downstairs as a child on a cold crisp morning to see a warm burning fire, courtesy of Mel’s early morning sacrifices. As her father left for work, she vividly remembered him saying: “Don’t let the fire go out.”

Alex Kercher | Feb 27, 2025 at 10:08 am

Wow this was powerful and well researched. Knowledge of our local political situation is huge for us students, especially as we get closer to voting age. Thank you for the incredible article and for calling attention to the disparities between policies Missourian’s want vs the people who get elected