Against Your Intuition: Lie Detecting

Discovered the difference between deceiving and lying to someone along with other alternatives of more trustworthy methods of understanding lying behavior

There are limitations to lie detector tests, uncover why many researchers don’t recommend it solely as a reliable source.

December 8, 2022

Liars. Deceivers. Equivocators. They’re all around us, and I’m betting that you know one. There are countless ways to weed liars out, but the most controversial method for more serious situations is partaking in lie detector tests. Now brings the question, what is the difference between deceiving and lying to someone? What are the alternatives to more trustworthy methods of understanding lying behavior? To uncover the truth behind lie detectors and why most psychologists don’t trust the method, along with lying in general.

Something can be considered a lie if it is notably not true, or deceitful. A lie is created when the speaker knows the truth and then chooses to present either an opposing side, or something similar, yet still false. From time to time there are displayed behaviors, (that sometimes go unnoticed), proving that the speaker is trying to deceive their audience. Deceiving is very similar to lying, as it is commonly a shared action.

Researcher John Reid wrote a bit on the topic of behaviors specifically known to be displayed by both liars and innocents during a lie detector test.

“Naturally, no specific type of behavior–even though it is highly typical of one or the other group–should never be considered proof of guilt or innocence, because there are or may be some exceptions to each general rule,” Reid wrote. “Nevertheless, an examiner will find it helpful at times to consider the probable significance of a subject’s behavior pattern. As might be assumed, a guilty subject is usually far from anxious to take a lie detector test.”

Some of the limitations to a lie detector test include the fact that there aren’t any physical, or even psychological reactions that are specific enough to fall into the category of deception, thus making it a bit more difficult to tell when a subject is fully lying vs plainly deceiving an examiner.

As for detecting lying behavior outside of lie detector tests themselves, few psychologists have recognized behaviors they look out for specifically. Of these behaviors, the most obvious have been mentioned by Richard Gray, the Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice at Fairleigh Dickinson University.

“The basic ideas—that a liar won’t look you in the eye, that they are more nervous than truth tellers, and that they will fidget and adopt odd postures—have a certain intuitive appeal. In fact, many of these behaviors are associated with feelings of guilt, nervousness, and lack of respect… The other place where these signs may be valuable is for short periods where an otherwise well-prepared liar has not rehearsed some part of the story and has to think up something on the spot,” Gray stated.

Although some psychologists and researchers also disagree with statements similar to Gray’s and state that there is not research backing up the documentation of the ‘Pinocchio response,’ a response in which all people across all situations “To date, no [research] has documented a ‘Pinocchio response;’ that is, a behavior or pattern of behaviors that in all people, across all situations, is specific to deception… All the behaviors identified and examined by researchers to date can occur for reasons unrelated to deception,” Mark Frank documented. The authors also mentioned that cognitive clues are huge for liars, as it relates to their feelings as well as emotional clues that they present without acknowledging. This further develops the point that everybody thinks differently, as even in the psychological community, not everyone has the same research plans, or documents backing up the facts they heavily believe in.

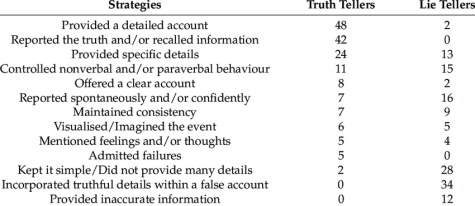

A handful of researchers compiled a few behaviors that both innocents and liars display, including those relating to fidgeting.

“The suspects blinked less frequently and made longer pauses during deceptive clips than during truthful clips. Eye contact was maintained equally for deceptive and truthful clips. These findings negate the popular belief amongst both laypersons and professional lie detectors (such as the police) that liars behave nervously by fidgeting and avoiding eye contact,” wrote Samantha Mann. Mann, Aldert Vrij, and Ray Bull all work closely with the Department of Psychology and the University of Portsmouth. They all have studied deception and behaviors presented in those who lie.

“First, self- and social-image concerns have been suggested as one possible explanation for partial lying. Some people engage in partial lying in order to maintain a positive image of themselves… In addition, people want to be perceived as credible and not as greedy, by themselves as well as by others,” Julian Conrads wrote, agreeing with the same thought. Conrads was a student studying management, economics, and social sciences at the University of Cologne Graduate School. Conrads also added that the reported subject’s behavior might also be influenced by the idea that their social image changes how many of their lies are believed.

You would probably think that policemen, federal agents, and all those occupying similar security careers would be the best at detecting liars, but you would be mistaken.

“[Researchers] have typically found that [security career holders] too are not any more accurate in their abilities to spot deception than lay people,” said Frank.

Frank also added, “These individuals had a kind of genius with respect to the observation of verbal and nonverbal clues… The expert lie detectors were labeled “truth wizards” to suggest their special talent. Although this term is unfortunate in mistakenly suggesting that their abilities are due to magic rather than talent and practice, the term does reflect the rarity of their abilities.”

“The first group identified [of the truth wizard variety] was a group of Secret Service agents who not only were superior, as a group, in detecting lies about one’s emotions, but those who were more accurate were more likely to report using nonverbal clues than those who were less accurate,” Frank wrote, proving that it comes with talent and practice to understand when somebody is lying, of which Secret Service agents have a lot of experience with.

Although there are the lucky few out there that have the talent of immediately understanding when somebody is lying, many interrogators wish they had that capability. Until then, they will contentiously stick to using lie detectors and hopefully move towards practicing psychologist-recommended methods.