‘You’re Just Gonna Get In Because You’re Ethnic’

Students of color share their experiences with the college application process

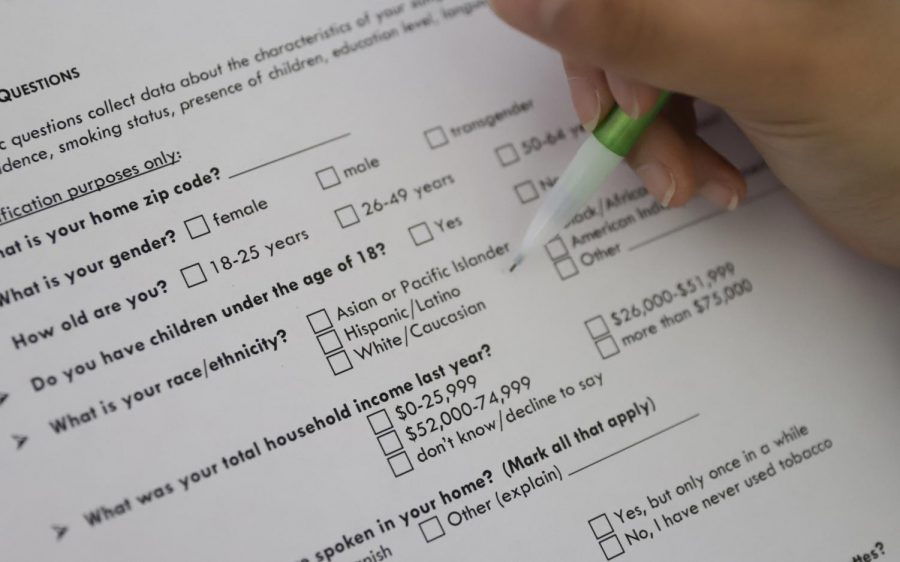

Some students of color are confronted with the accusation that it is easier for them to get into college.

April 19, 2021

For students of color, education is highly prioritized and defended by their family values. Especially for first generation students, there is an added emphasis for a college degree, as it may not be as accessible in other countries as it is in the United States. Senior Liam Merino feels his family background has impacted his view on schooling.

“It’s definitely like it’s just a like immigrant mentality, that you need an education,” Merino said. Merino’s parents hail from Colombia and Mexico, and while he has found it impacting his upbringing, this past year he has noticed it taking effect on his college application process. Additionally, as the eldest child, he is the first person in his family to attend college in the U.S.

“I had no idea how anything worked here,” Merino said. He found himself faced with a different process than what his family faced: his preparation for the ACT, a college entrance exam accepted by all schools, contrasted the separate entrance exams for each school that his parents were required to take.

Merino’s preparation included engaging in rigorous AP courses that tailored to his major of interest: computer science. He joined organizations such as the Technology Student Association (TSA) and kept his goal of postsecondary education in mind. However, despite his efforts, he was met with backlash, accusing him of an easy path to college due to his race.

“You’re assumed you’re gonna go somewhere good just because of who you are, not what you’ve done,” Merino said.

Other students have attributed his success to his ethnicity, pointing a finger at affirmative action policies in college admissions. These policies are often misconceived as a way to put under-qualified persons in jobs or college; however, affirmative action consultant and owner of EEO Consulting in St. Louis Judy Julius dispels this misconstrued look at the policies.

“My definition of affirmative action is to remedy disparities in the workplace, simple as that,” Julius said. With over 40 years of experience in writing affirmative action programs for federal contractors and subcontractors, Julius utilizes census data to ensure companies aren’t “underutilized,” or not using females or minorities as much as they could. She embraces the consideration of factors such as race and gender in employment processes.

“Any good diversity, equity and inclusion person will tell you that if you embrace diversity at all levels of your organization, you will have a more profitable company,” Julius said. “So I think that it helps the company, but I certainly think that it helps the employees.” She notes that universities follow different regulations, but are under the same concepts.

Despite these benefits, the misconception still persists, pushing students of color to feel as if they have to prove themselves.

“I knew I had to just do good,” Merino said. “Because if I was just subpar in my classes and I got into college, people were going to be like, ‘Oh, it’s ethnic background.’”

Some students of color don’t face as much confrontation, but still feel the judgment when it comes to admissions. These students find themselves in a position of criticism, even though they didn’t place themselves there.

“Even if I didn’t see myself as a person of color, everybody else definitely does,” senior Halima Lahrdiri said.

Like Merino, Lahrdiri’s upbringing placed a heavy emphasis on education, and she is also the first in her family to attend college in the United States. Personally, she hasn’t faced accusations of being accepted to college solely due to race, but witnesses people like her endure those types of injustices.

“It’s especially those people that don’t get the benefits that always have something to say,” Lahrdiri said.

According to Julius, this misconception has no merit—and no benefits. If a university accepts an under-qualified student, they are going to have trouble succeeding. This myth breeds further effects on people of color, adding onto the stress they face from receiving these accusations.

“They are always going to carry this somewhat of a burden of people looking at them as not as qualified because of their gender or their race,” Julius said. “Which leads you to another perception that minorities have to work twice as hard to get as far as somebody.”

Luckily, Merino has been able to work past this burden, and apply it to his process.

“You have to take that as fuel to do better,” Merino said.

As the 2021 college admissions cycle wraps up, the stigma surrounding students of color still stands. In U.S. history, cases like Fisher v. University of Texas in which a UT-Austin applicant claims she was rejected due to the college’s acceptance of minority students, racial discrimination has been evident. However, Julius has faith in the class of 2021.

“I think that your generation is doing a much better job of not caring about a person’s race, not caring about a person’s gender, not caring if people are transgender, not caring about their sexual orientation,” Julius said. “Having worked in this field for 40 years, I am beyond disappointed on how far we haven’t come.”